By Aarti Sahasranaman, Vice President, Interventions – ICTPH

Since 2008, Sangath, a non-profit organisation based in Goa, working in the field of child development, adolescent health and mental health has been organising a course on “Development and Evaluation of Complex Health Care Interventions”. In addition to pioneers in the field of public health who share their specific experiences, the course is taught in collaboration with faculty from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) and the South Asia Network for Chronic Diseases (SANCD). This year, the Complex Interventions course was held from 7th – 12th November at the International Centre, Goa. There were a total of 34 participants including five from ICTPH – Selva Swetha, Vani Priya, Mayank Kedia, Arun Jithendra, and Aarti Sahasranaman. Participants were from diverse backgrounds, ranging from professionals in government organizations with years of experience in evaluating complex interventions, founders/leaders of NGOs in the field of public health, to individuals from non-public health backgrounds interested in learning the language of intervention design and evaluation. The primary objectives of the course, therefore, were to provide all participants with an understanding of what complex interventions are, standard frameworks to be used in the design of such complex interventions, and finally methods to be used in the evaluation of these interventions. The mode of instruction throughout the course was very interactive, and participants were encouraged to share their experiences and learnings from the field, to provide real-life instances of complex interventions.

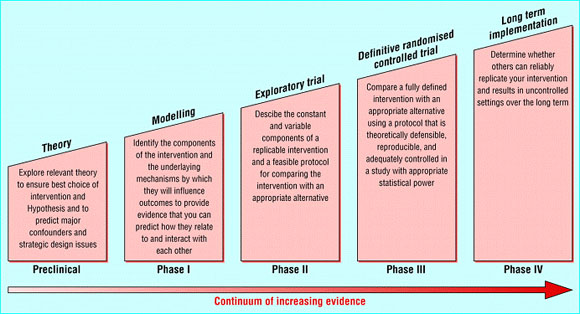

So, what exactly distinguishes a complex intervention from a simple one, and are there in fact any public health interventions that are anything less than complex? A complex intervention can be thought of as a conglomeration of multiple components (elements or interventions) that must be employed to achieve a desired outcome. However, a complex intervention is more than just the sum of its parts, especially since it is very difficult to tease out the so-called “active ingredient” of a complex intervention. The complexity of an intervention is a function of multiple factors – the number of components, the nature of the components (behaviour change interventions, for example, can be notoriously complex), the range of human resources required and interactions among them, the number of possible outcomes, and so on. Thus, it turns out that most, if not all, public health interventions are complex since targeting even an individual health outcome requires coordinated efforts at multiple levels. The first session of the course, therefore, focused on bringing all participants to a uniform understanding of what defines a complex intervention. This session was anchored by Dr. Vikram Patel, co-founder and board member of Sangath, and Professor of International Mental Health and Wellcome Trust Senior Clinical Research Fellow at LSHTM. Dr. Patel introduced us to the Medical Research Council (MRC) of UK’s framework for the development of complex interventions. The MRC framework released in 2000 envisioned a linear, five-step process for the development and evaluation of complex interventions, as shown below.

Source: Campbell, M et al. (2000). MRC framework for evaluating complex interventions. BMJ 321: 694 – 696.

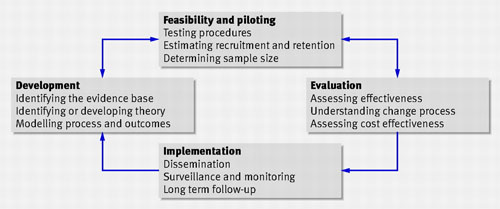

As is evident from the image above, this model is not very flexible and does not allow for refinement of intervention design as we go along the continuum of increasing evidence. In light of this and other deficiencies, the MRC developed an improved framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions in 2008, as shown below. This new model is more flexible and certainly more iterative, as can be seen. Furthermore, it also emphasises on a variety of methods for evaluation of interventions, going beyond the norm of evaluation using randomised controlled trials (RCTs) set by the 2000 MRC framework.

Source: Craig, P et al. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 337: a 1655.

For the first three days of the course, during the morning sessions we were taught in some depth about each step involved in intervention design as laid down by the MRC framework. Besides Dr. Vikram Patel, who introduced us to the MRC framework and taught the module on formative research and piloting, our other instructors included Dr. Madhumitha Balaji who handled the theory building and modelling session, and Dr. Shah Ebrahim, Professor of Public Health at LSHTM and Director, SANCD who gave us a very interesting lecture on evaluation of interventions. Having instructors who have been involved in developing and evaluating complex interventions share their personal experiences was definitely a highlight of the course. The afternoon sessions of the first three days involved group work of case discussions. Groups had been formed at least two weeks prior to beginning of the course, and case studies were allotted to groups. Case studies were carefully chosen to reflect the specific aspect of intervention design or evaluation that had been covered during the morning session. Each group analyzed the case study assigned to them aided by guidelines provided by the course organizers. The last hour was spent with a representative from each group making a short presentation on the case study, followed by a brief discussion. The group discussions of case studies provided a great opportunity for each of us to identify and clarify gaps in our understanding of intervention design, while also being exposed to the perspectives of other group members with varying levels and kinds of experience in intervention design and evaluation.

The last three days of the course were particularly motivating with pioneers in the field of public health in India talking about their journeys as they developed and implemented much-needed public health interventions, some of which have now changed the health landscapes of communities across the country. While all talks were much appreciated, the most outstanding and inspiring talk, in my opinion, was definitely that of Dr. Abhay Bang of SEARCH, Gadchiroli. Dr. Bang and his wife, Dr. Rani Bang, inspired by Gandhian thought, started SEARCH (Society for Education, Action, and Research in Community Health) in 1985 after having returned from the United States where they received Masters degrees in Public Health at Johns Hopkins University. They envisioned SEARCH to be an institution of community health that acted as a healthcare provider to rural populations, in addition to carrying out research that could inform the global public health community. Dr. Bang shared with us the story of the development of the Home Based Neonatal Care (HBNC) intervention, which was designed when he experienced first-hand the consequences of the absence of accessible neonatal care in the rural community of Gadchiroli. He surmised that given the cultural practices and beliefs of the population and the inaccessibility of healthcare services, what was needed was a model where neonatal care could be provided at home by trusted service providers. The HBNC model involves task shifting, where village health workers are trained in neonatal care, including management of neonatal sepsis, a major cause of neonatal mortality, and they take healthcare into the homes of neonates. A point of controversy with this intervention was the fact that village health workers with no medical knowledge per se were being trained to provide antibiotic injections to infants. Evaluation of the HBNC intervention revealed that over a three-year period, HBNC reduced infant and neonatal mortality by over 50% in certain rural populations. After spending over six years demonstrating the efficacy of HBNC, and many years since then talking to people and government organisations convincing them of the replicability, scalability, and ethical propriety of the model, the HBNC model has been adopted in an abridged version in the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM). In the NRHM version, ASHAs (accredited social health activists) will provide home-based neonatal care. However, they will not be trained to provide antibiotic injections, a key component in the management of neonatal sepsis. Whether this will be as successful as the original HBNC model remains to be seen. As Dr. Bang walked us along his personal journey with the HBNC model, it became apparent that it was the combination of correctly identifying a pressing need in the community and coming up with an acceptable intervention to meet that need that was ultimately responsible for the spectacular success of the programme. Additionally, adequate training of the village health workers and constant monitoring of their activities ensured that the quality of the programme was not compromised at any step. As we develop appropriate interventions for our communities and deliver them through our trained AYUSH physicians and health extension workers (HEWs) at our RMHCs, keeping these lessons in mind will serve us well.

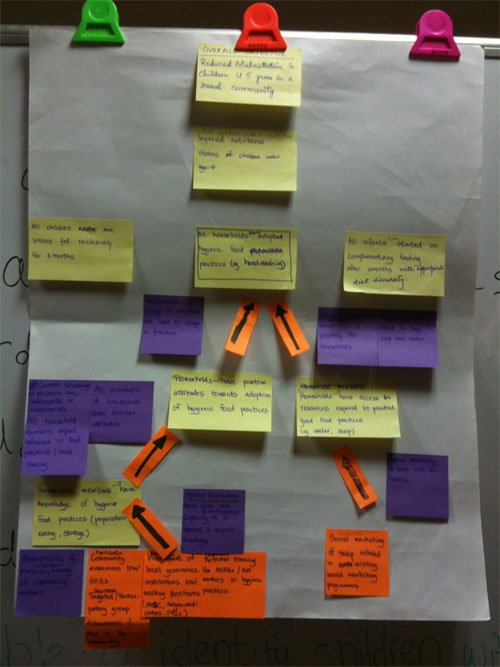

In addition to real-life case studies, we were also involved in group work during the last three days of the course. Our task during group work was to develop a framework for an intervention using the newly developed “theory of change”, which can be thought of as a theory or story of how our intervention will have the large social or health impact we visualise. We were introduced to the concept of ToC by Dr. Mary De Silva who recently attended a workshop on the subject. Interestingly, while ToC has been used for to develop and evaluate comprehensive community initiatives, it has not been widely used for design of healthcare interventions, thereby making our exercise rather novel. In general, when we design interventions, our starting point is an intervention that we think will work and we end by evaluating whether the intervention did in fact have the desired impact. This approach might actually affect our ability to achieve the impact we desire because we might start with an intervention, which while successful elsewhere, might be sub-optimal in our context. Instead, ToC contends that by starting with a vision of where we want to be, a realistic understanding of where we are, and a plan for bridging the gap between the two, we are far more likely to achieve our goal. Theory of change is, in essence, the roadmap that will guide us along this path. To construct a ToC map for design and evaluation of an intervention, we begin by deciding on the impact we want to make in the world. In the next step, we work backwards to decide on all possible outcomes that are absolutely needed for the goal to be achieved. At this step, we focus only on outcomes, not interventions. Next, we explicitly mention all assumptions and rationales underlying our expectations that a specific outcome will lead to the one above it. Being aware of all the assumptions we are making will also provide us with a very focused set of issues that can be addressed in the formative research phase. For each outcome, we then choose at least one indicator to measure whether that outcome has been achieved. Only when all of these steps have been completed do we add intervention components that will be needed to achieve each outcome. At this point, we also pencil in key activities that are required to make each component of the intervention happen. When designing the ToC roadmap, mapping interventions might turn out to be the fastest step in the process because we are already very clear about the outcomes we are trying to achieve and the indicators we will use to measure these outcomes.

Based on suggestions from participants, three topics for intervention design and evaluation were chosen for group work for the last three days. These were interventions to reduce malnutrition among children under the age of 5 years in a rural community (shown below), to promote sexual health among adolescents in urban areas, and for the rehabilitation of individuals with spinal cord injuries. Since the idea of ToC was new to all participants, group work proved to be rather interesting as it forced all of us to confront our individual misconceptions of the concept. By actually working through entire causal pathways (complete with assumptions and rationales) that would result in the achievement of our goal, it became possible for us to appreciate the real value of constructing a ToC roadmap.

Theory of change map to reduce malnutrition among children below the age of 5 years in a rural community. Yellow post-it notes reflect outcomes, purple post-its are assumptions/rationales, and interventions are written on orange post-it notes.

Our week-long participation in the Complex Interventions course has helped all of us return with a clearer idea of the research methodologies involved in the design and evaluation of public health interventions. While most of us were favourably biased towards quantitative research before we attended the course, I believe that we now have far greater appreciation for qualitative research and the value it can add to improving the design and delivery of interventions. We also realised that one of the most obvious omissions in our intervention design methodology has been the lack of solid formative research, which could potentially help us avoid a lot of heartache with respect to how our interventions are perceived and accepted by members of the community. The message that carefully evaluating pilots is an important aspect of tweaking intervention design has not been lost on us. Since our return, we are working with Aimee Latta, an intern, to develop an evaluation framework for the CVD intervention, our longest running intervention. In future, we plan to develop such evaluation frameworks to measure the impact each of our interventions have had on the health of our communities. Finally, one of the most important learnings for all of us in this course has been the theory of change. While the thought of spending months designing a ToC map initially appeared to be somewhat of a frivolous academic pursuit, having done the group work, I stand convinced that there is definitely value in this exercise. One simple example is that the ToC forces us to confront and therefore eventually test all assumptions that we make while designing complex interventions. The most complex of interventions can come unravelled by a simple but erroneous assumption. Spending time thinking through the design phase of an intervention will definitely help us avoid the very real danger of developing interventions which do not achieve the desired impact. At the end of his talk, Dr. Bang told us that each of us had to find our own motivation, a reason for wanting to work in the field of public health. As a follower of Gandhian thought, Dr. Bang was guided by his spirituality. As individuals in an organisation, our reasons and motivations for choosing this field might be varied, but we are all, in my opinion, united in our belief that we must deliver the best healthcare services possible to the communities we serve. Thoughtful intervention design is a necessary first step to achieve this goal, and attending this course has certainly taken all of us a step closer in that direction.

Leave a Reply

2 Comments on "Development and Evaluation of Complex Health Care Interventions – Course Organised by Sangath, Goa"

This is an excellently writtten and thought provoking blog post Aarti. I agree with all that you have to say. It is really quite amazing that the very talented Sangath team, Vikram, Dr. Bank, Madhumita, year after year, take out time to offer this course.

Thank you, Nachiket. The Sangath team is indeed wonderful, and I must say that the entire experience was great for the whole team. We are all definitely much better placed to appreciate the nuances of intervention design and evaluation.